Modern applications routinely outgrow the assumptions of classical algorithms that expect all data to fit in main memory. In data-intensive systems, the dominant cost is moving and accessing data rather than computing on it, so scalability hinges on minimizing transfers and space. This chapter motivates that perspective, explains why “massive” is relative to resources and requirements, and sets the book’s goal: practical, hardware-aware techniques—grounded in theory yet implementation-friendly—that help engineers design scalable solutions for large, evolving datasets across real-world pipelines.

A concrete example with billions of news comments shows how straightforward hash-table approaches quickly demand tens to hundreds of gigabytes, motivating more compact, approximate alternatives. The chapter previews succinct data structures for core questions: Bloom filters for membership with small false-positive rates, Count-Min Sketch for frequency estimation and heavy hitters using a fraction of the space, and HyperLogLog for precise-on-average cardinality estimates in kilobytes. It then broadens to streaming scenarios where one-pass constraints favor Bernoulli and reservoir sampling and quantile sketches (such as q-digest and t-digest) for real-time analytics, and to persistent storage where external-memory algorithms and database-backed structures (e.g., B-trees, Bε-trees, LSM-trees) are chosen to match read-, write-, or mixed-optimized workloads, including efficient external sorting.

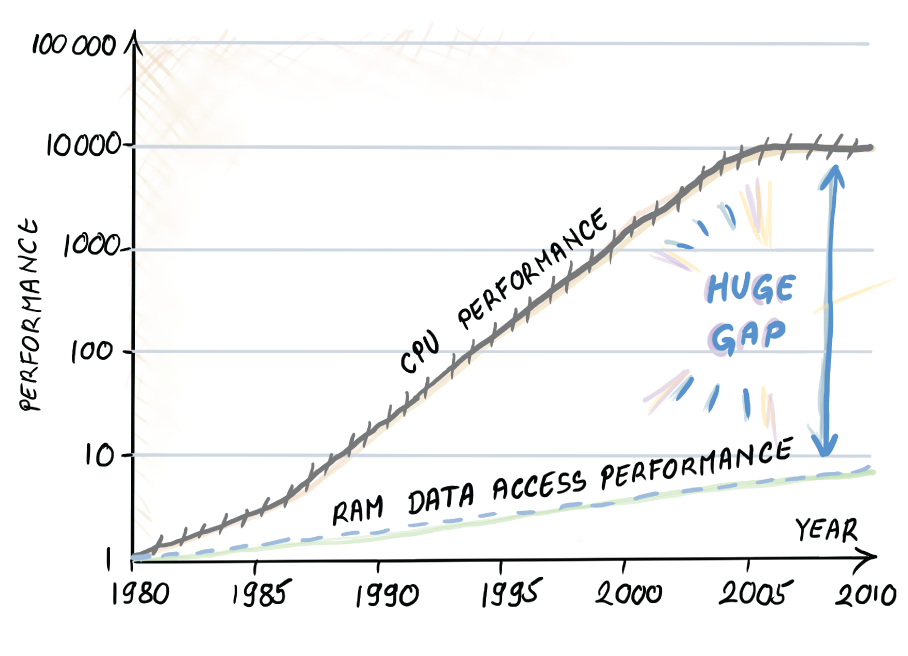

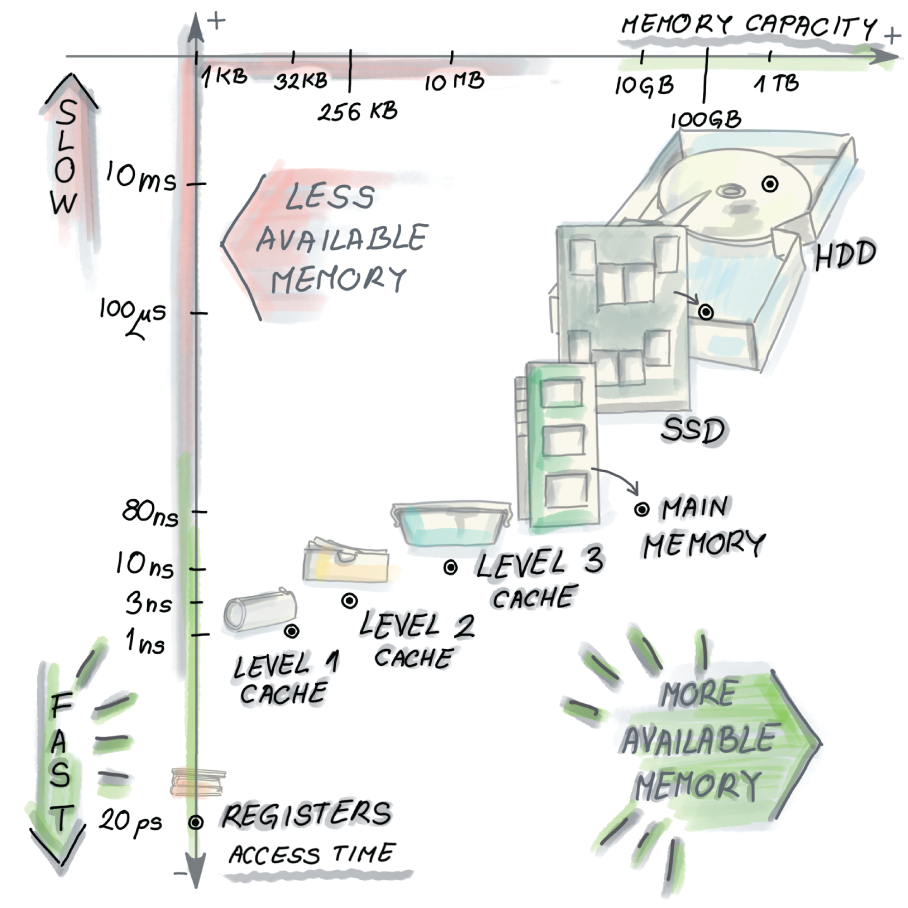

The chapter grounds these choices in hardware realities: the widening CPU–memory performance gap, a memory hierarchy trading speed for capacity, and the “latency lags bandwidth” principle, all of which reward sequential access, caching, and compact representations—summarized by the mantra that reducing space saves time. It also notes added delays in distributed systems and cloud environments, reinforcing designs that minimize random I/O and network hops. The book is organized into three parts: hash-based sketches, streaming and sampling methods with quantile estimation, and external-memory models with storage-engine data structures. It is intended for practitioners with foundational algorithmic knowledge who seek system-agnostic, scalable techniques they can apply at work.

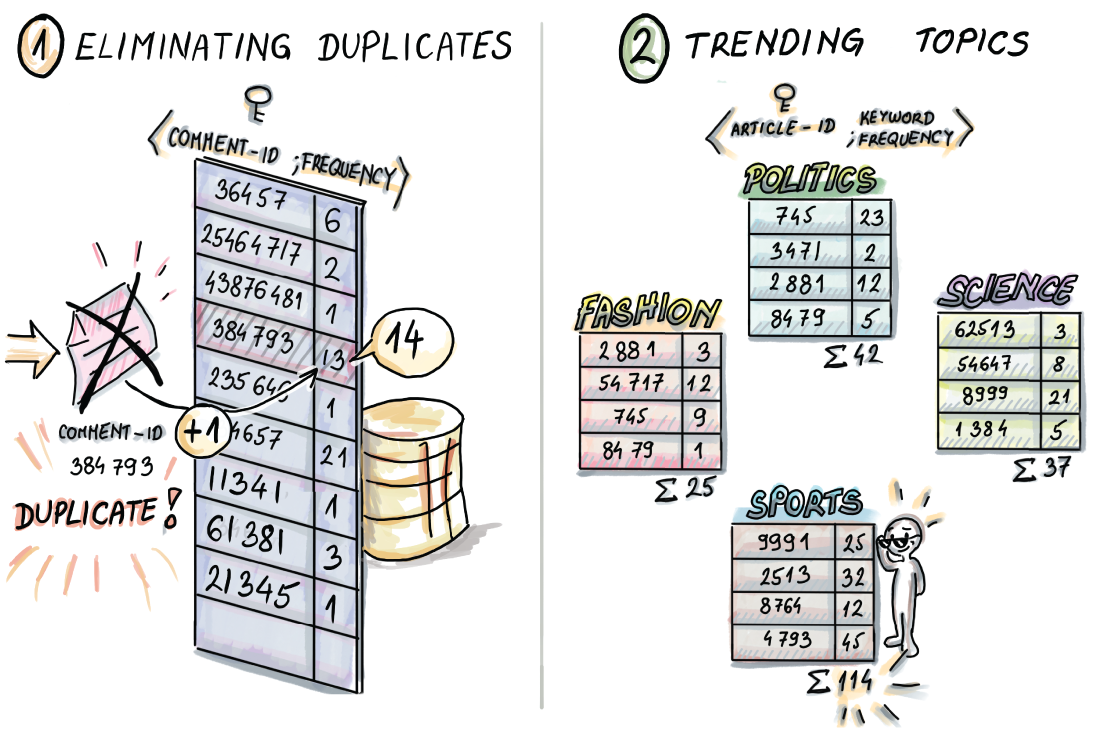

In this example, we build a (comment-id, frequency) hash table to help us store distinct comment-ids with their frequency count. An incoming comment-id 384793 is already contained in the table, and its frequency count is incremented. We also build topic-related hash tables, where for each article, we count the number of times associated keywords appeared in its comments (e.g., in the sports theme, keywords might be “soccer,” “player,” “goal,” etc.). For a large dataset of 3 billion comments, these data structures may require from dozens to a hundred gigabytes of RAM memory.

Most common data structures, including hash tables, become difficult to store and manage with large amounts of data.

CPU memory performance gap graph, adopted from Hennessy & Patterson’s computer architecture. The graph shows the widening gap between the speeds of memory accesses to CPU and RAM main memory (the average number of memory accesses per second over time.) The vertical axis is on the log scale. Processors show an improvement of about 1.5 times per year up to year 2005, while the improvement of access to main memory has been only about 1.1 times per year. Processor speed-up has somewhat flattened since 2005, but this is being alleviated by using multiple cores and parallelism.

Different types of memories in the computer. Starting from registers in the bottom left corner, which are blindingly fast but also very small, we move up (getting slower) and right (getting larger) with level 1 cache, level 2 cache, level 3 cache, and main memory, all the way to SSD and/or HDD. Mixing up different memories in the same computer allows for the illusion of having both the speed and the storage capacity by having each level serve as a cache for the next larger one.

Cloud access times can be high due to the network load and complex infrastructure. Accessing the cloud can take hundreds of milliseconds or even seconds. We can observe this as another level of memory that is even larger and slower than the hard disk. Improving the performance in cloud applications can also be hard because times to access or write data on a cloud are unpredictable.

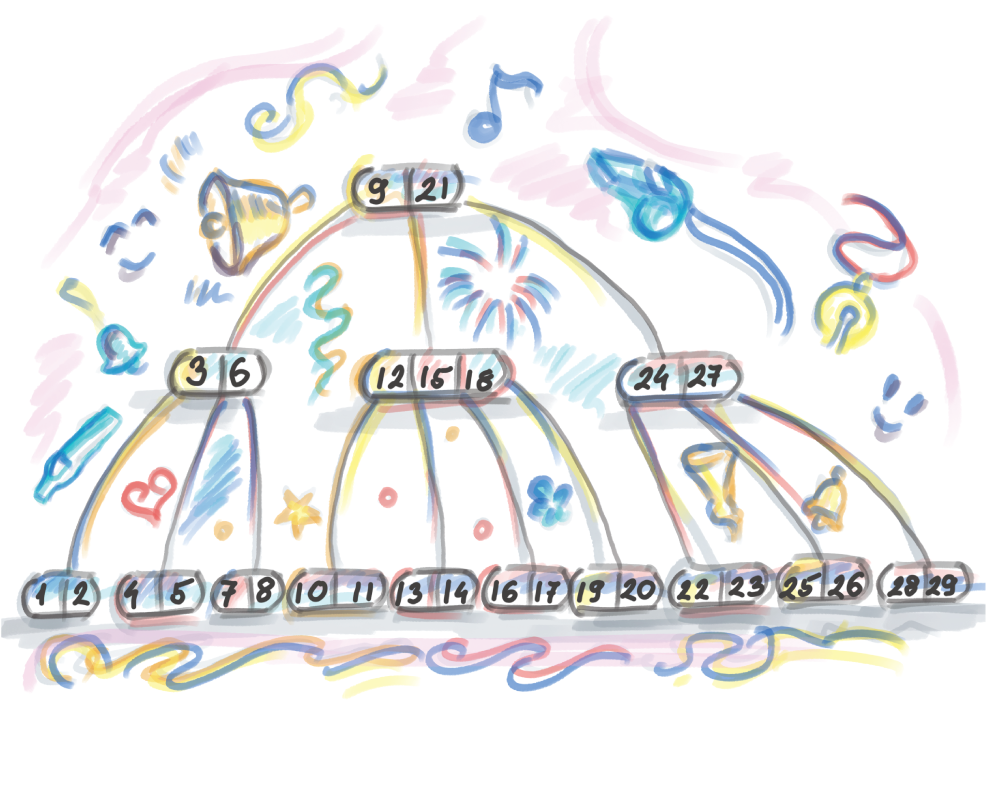

An efficient data structure with bells and whistles

Summary

- Applications today generate and process large amounts of data at a rapid rate. Traditional data structures, such as key-value dictionaries, can grow too big to fit in RAM memory, which can lead to an application choking due to the I/O bottleneck.

- To process large datasets efficiently, we can design space-efficient hash-based sketches, do real-time analytics with the help of random sampling and approximate statistics, or deal with data on disk and other remote storage more efficiently.

- This book serves as a natural continuation of the basic algorithms and data structures book/course because it teaches you how to transform the fundamental algorithms and data structures into algorithms and data structures that scale well to large datasets.

- The key reasons why large data is a major issue for today’s computers and systems are that CPU (and multiprocessor) speeds improve at a much faster rate than memory speeds, and the tradeoff between the speed and size for different types of memory in the computer, as well as the latency versus bandwidth phenomenon, leads to applications processing data at a slower rate than performing computations. These trends are not likely to change soon, so the algorithms and data structure that address the I/O cost and issues of space are only going to increase in importance over time.

- In data-intensive applications, optimizing for space means optimizing for time.

FAQ

What topics does Chapter 1 introduce and how is the book structured?

Chapter 1 outlines three themes that define the book:- Part 1 (Ch. 2–5): Hash-based succinct sketches (review of hashing, Bloom filters, Count-Min Sketch, HyperLogLog).

- Part 2 (Ch. 6–8): Data streams (Bernoulli and reservoir sampling, sliding-window sampling, quantile sketches such as q-digest and t-digest).

- Part 3 (Ch. 9–11): External-memory algorithms and storage (I/O-efficient searching/sorting, B-trees, Bε-trees, LSM-trees).

How are algorithms for massive datasets different from “classical” algorithms?

Classical analyses assume data fits in RAM and focus on CPU steps (Big-O). With massive data, the bottleneck is moving and accessing data, not computing on it. This shifts emphasis to space efficiency, approximate answers (sketches), cache-aware access patterns, and external-memory models that minimize costly transfers.What qualifies as a “massive dataset” for this book’s techniques?

It’s relative. Size alone doesn’t define it; hardware budget, workload, and performance requirements matter. Teams with modest datasets but tight memory or stringent latency can benefit, and even resource-rich organizations adopt space-efficient structures to stretch RAM.Why do common in-memory data structures become problematic at scale?

Per-item overhead accumulates. For example, a hash-based dictionary over billions of items can consume tens of gigabytes once you include keys, counts, and table overhead. Multiple such structures (e.g., per-topic indices) quickly exceed RAM, complicating performance and operations.Which succinct data structures can replace large hash tables and what trade-offs do they make?

- Bloom filter: answers membership with a small false-positive rate, using far less space (e.g., order-of-magnitude reduction) because it stores bit patterns, not keys.

- Count-Min Sketch: estimates frequencies with one-sided (over)error, using dramatically less space than key-count hash maps; also useful for per-topic keyword counts.

- HyperLogLog: estimates cardinality with small relative error using kilobytes of memory.

In the comments example, why does a naive dictionary approach hit memory limits?

Counting distinct comment IDs and maintaining per-topic keyword tables for billions of comments requires many key-value entries plus hash-table overhead. Summed across tasks (deduplication, topic counts), this can approach or exceed available RAM, making updates and queries slow or infeasible.How does the streaming setting change solution design?

With high-velocity events (e.g., new comments, likes), you often can’t store everything or rescan later. One-pass, low-memory techniques are needed: Bernoulli/reservoir sampling for aggregates; sketches for heavy hitters and quantiles (e.g., t-digest). Results are approximate but timely and resource-efficient.What hardware realities make massive data hard?

- CPU–memory speed gap: computation outpaces data access.

- Memory hierarchy: fast memories are small; larger memories are slower (caches → RAM → SSD/HDD).

- Latency vs. bandwidth: bandwidth improves faster than latency; many small random accesses are costly.

- Distributed systems: network hops add unpredictable delays on top of local storage costs.

What are external-memory algorithms and when should I use them?

They target data on SSD/HDD/cloud, minimizing slow transfers by batching and sequential access. Use them for large persistent datasets (e.g., databases, indexes) and workloads that need accurate queries but tolerate disk latency. Structures include B-trees, Bε-trees, and LSM-trees, tuned for read-, write-, or mixed-optimized workloads.How should I design algorithms with hardware in mind?

- Reduce space to save time (fit summaries in fast memory, avoid random I/O).

- Favor sequential over random access; exploit cache lines/pages/blocks and spatial locality.

- Lay out data to minimize transfers and leverage bandwidth.

- Balance scalability with other system concerns (security, availability, maintainability).

Algorithms and Data Structures for Massive Datasets ebook for free

Algorithms and Data Structures for Massive Datasets ebook for free