1 Understanding data-oriented design

Game development demands fast, responsive experiences under strict performance budgets and shifting requirements. Data-Oriented Design (DOD) addresses these realities by taking a data-first approach: organize data to suit how modern CPUs actually run code, separate data from logic, and treat features as transformations of explicit inputs into outputs. This mindset consistently improves performance, readability, and extensibility across AAA, indie, and mobile projects, turning “premature optimization” into naturally efficient code rather than late-stage fixes.

The core performance win comes from aligning data layout with CPU caches. Instead of scattering fields across object graphs, DOD pursues data locality so hot data sits contiguously in memory and arrives in cache-line-sized chunks, maximizing cache hits and minimizing stalls to main memory. Patterns like processing arrays of positions, directions, and velocities in tight loops let cache prediction do its job, dramatically accelerating simple systems such as moving thousands of enemies per frame. By focusing on where data lives, not just what code does, DOD transforms memory access from a bottleneck into a strength.

To reduce complexity and improve extensibility, DOD separates data and logic and frames features as “input → transform → output.” Instead of inheritance trees, new behaviors are added by introducing the minimal data needed and writing straightforward functions that operate on that data—keeping cost flat even as features multiply. While Entity Component System (ECS) can be used to implement DOD (entities as indices, components as data, systems as logic), the approach is not tied to any pattern; teams can adopt whatever file and module organization fits best. In practice, DOD combines three pillars—data locality for speed, data/logic separation for clarity, and data-first problem solving for scalability—yielding code that stays fast and adaptable over a game’s lifetime.

Screenshot from our imaginary survival game, with the player in the middle, and enemies moving around.

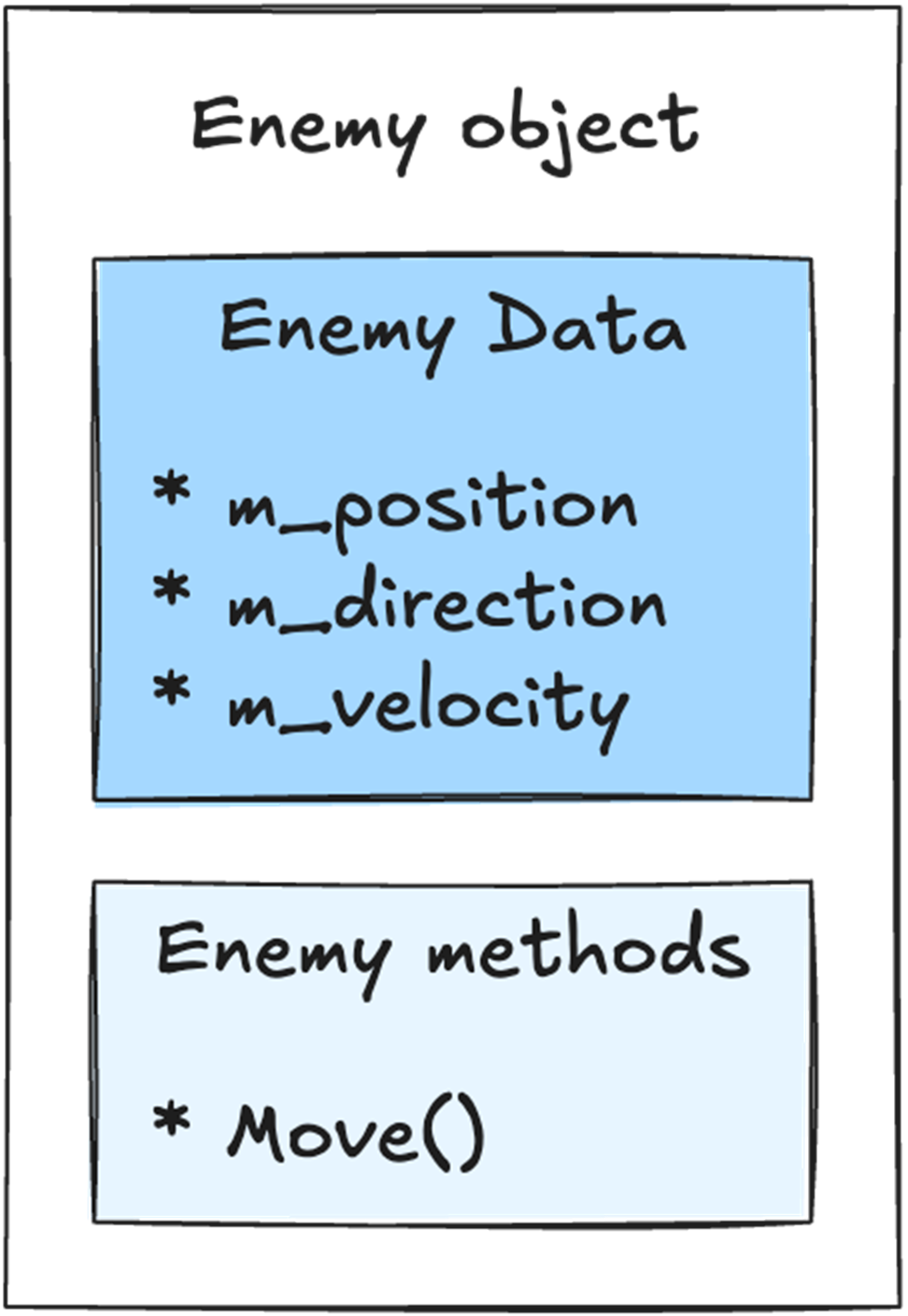

Our Enemy object holds both the data and the logic in a single place. The data is the position, direction, and velocity. The logic is the Move() method that moves this enemy around.

On the motherboard, the memory sits apart from the CPU, regardless if it’s in a console, desktop and mobile device. That physical distance, combined with the size of the memory, makes it relatively slow to retrieve data from memory.

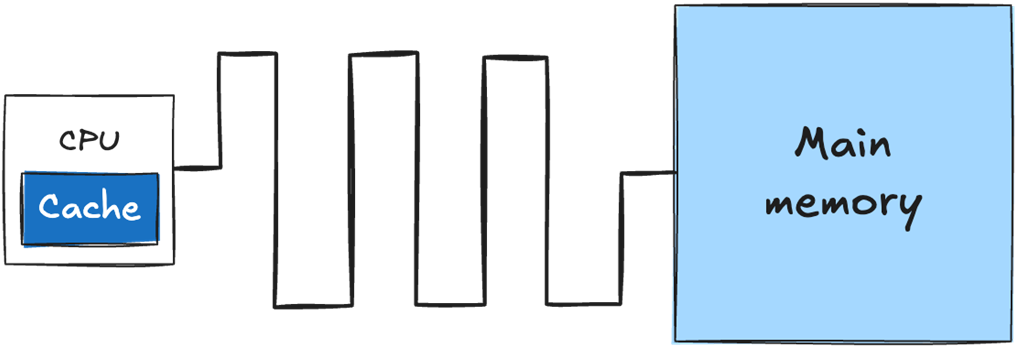

The cache sits directly on the CPU die and is physically small. Retrieving data from the cache is significantly faster than retrieving data from main memory.

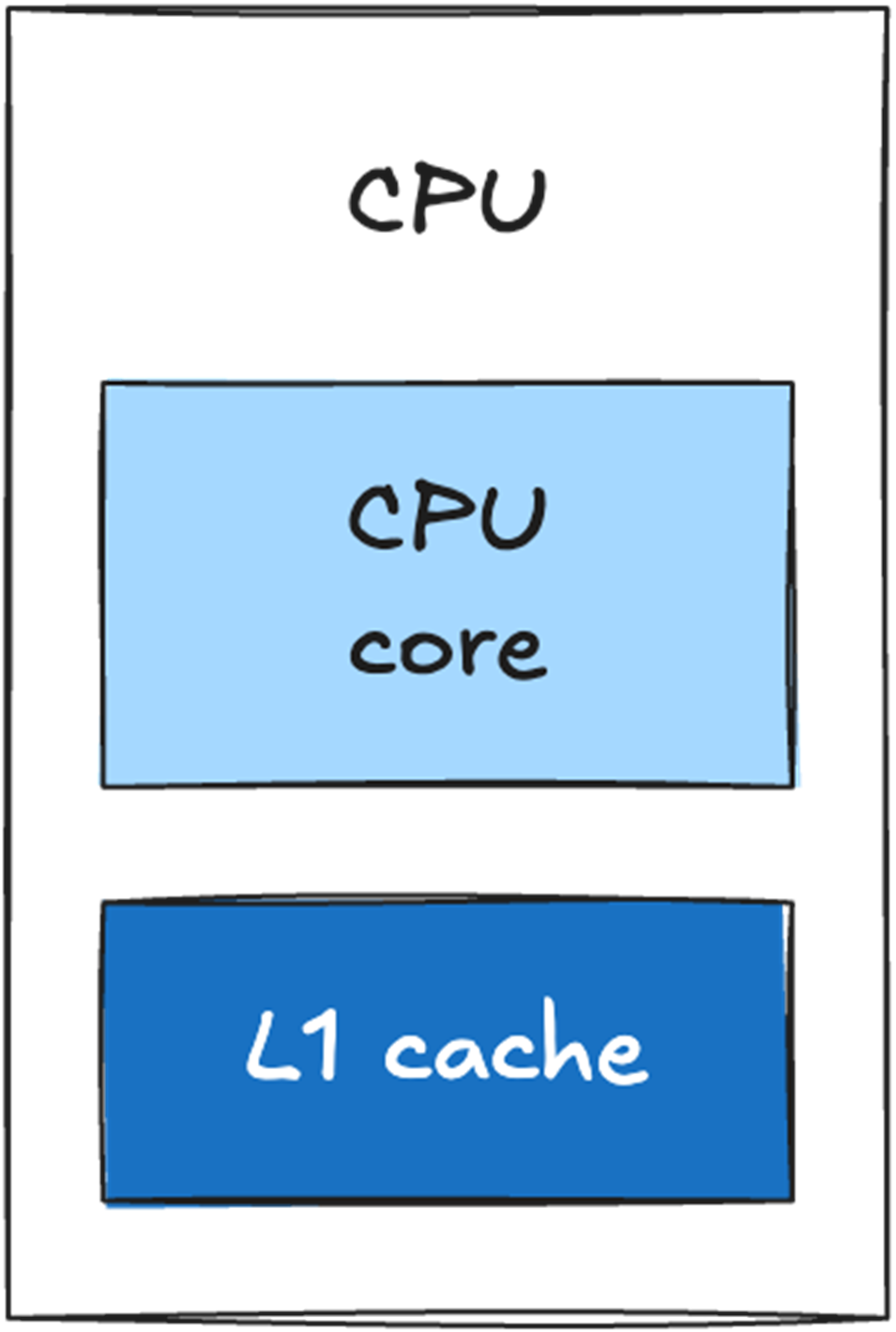

A single-core CPU with an L1 cache directly on the CPU die.

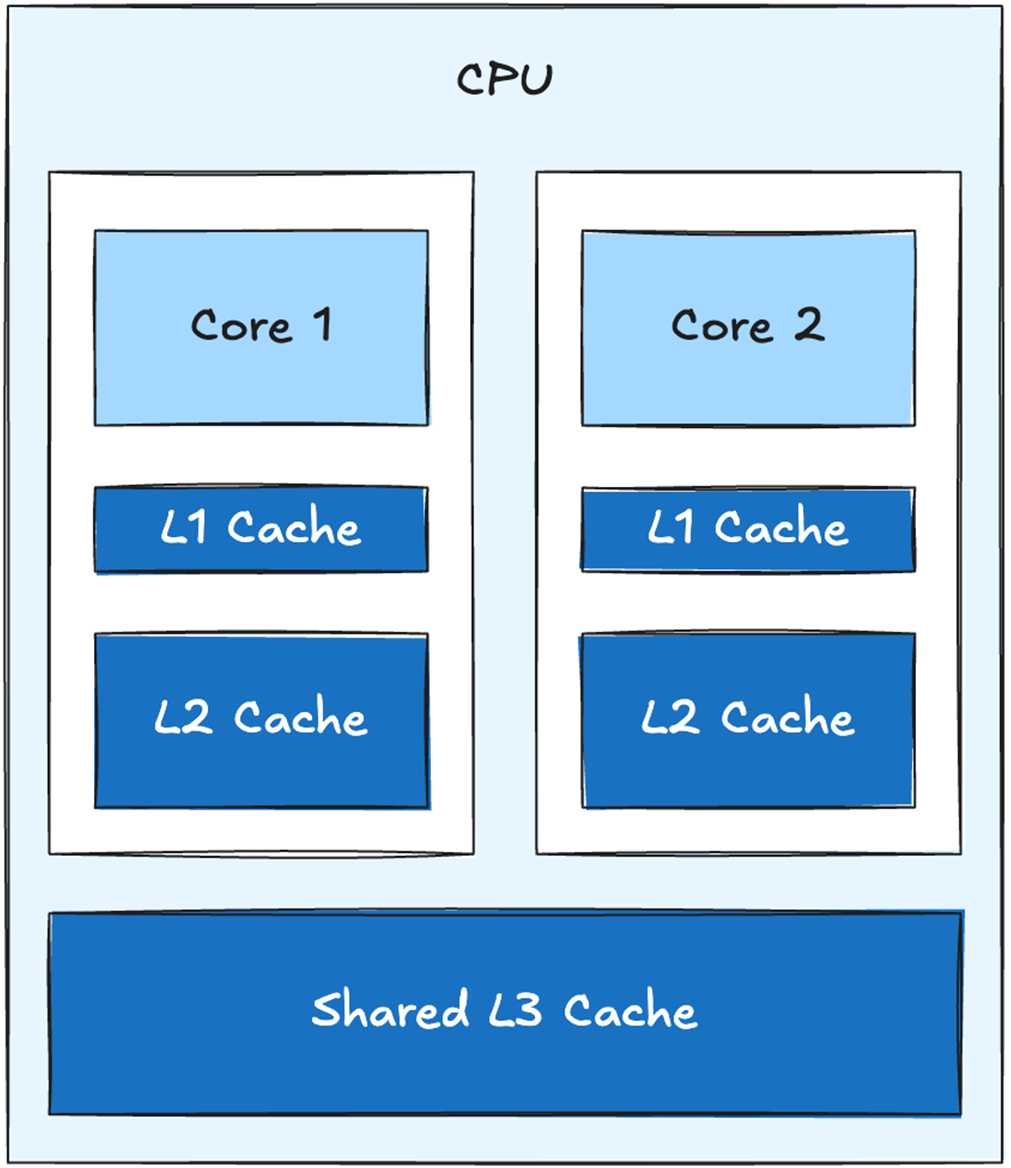

A 2-core CPU with shared L3 cache

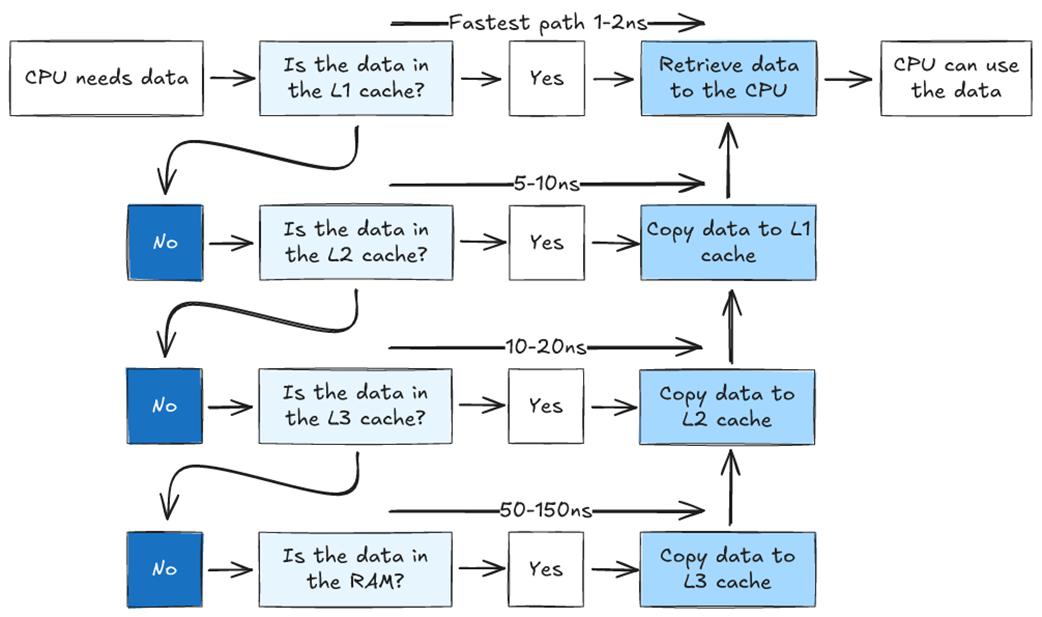

Flowchart showing how the CPU accesses data in a system with three cache levels. If the data is not found in the L1 cache, we look for it in L2. If it is not in L2, we look in L3. If it is not in L3, we need to retrieve it from main memory. The further we have to go to find our data, the longer it takes.

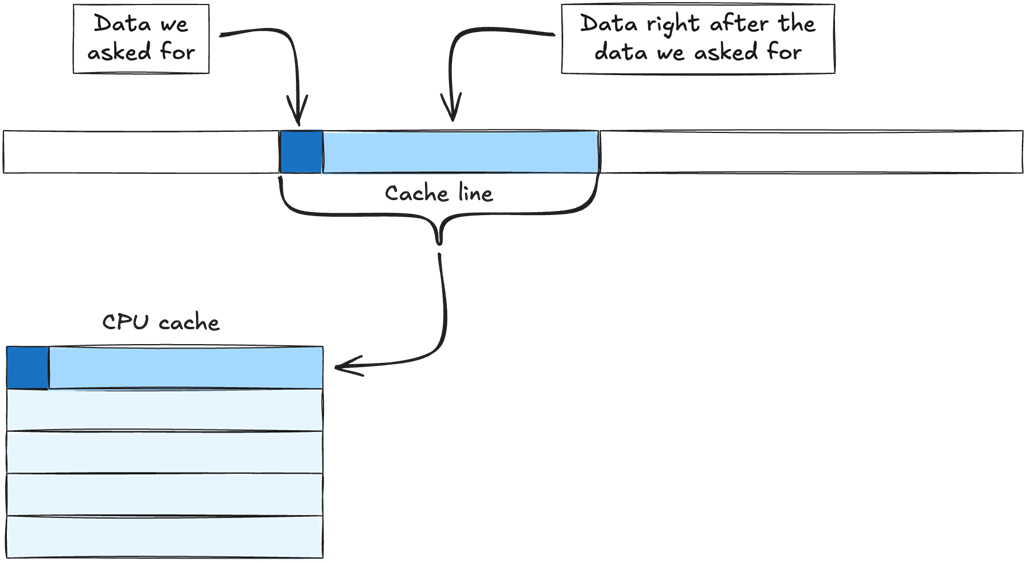

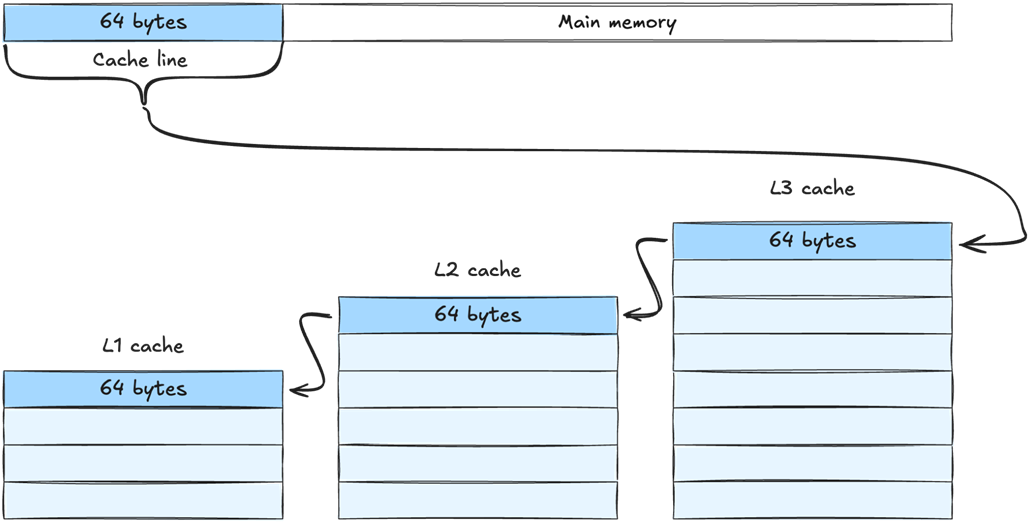

Data is retrieved from main memory in chunks called cache lines. When we ask for data from main memory, the memory manager retrieves the data we need, plus the chunk of data that comes directly after it, and copies the entire chunk to the cache.

When retrieving a cache line from main memory, it is copied to all levels of the cache. In this example it is first copied to L3, then L2 and finally L1. The cache line is the same size at all levels - meaning the same amount of data is copied to every level. L3 can simply hold more cache lines than L2, and L2 can hold more cache lines than L1.

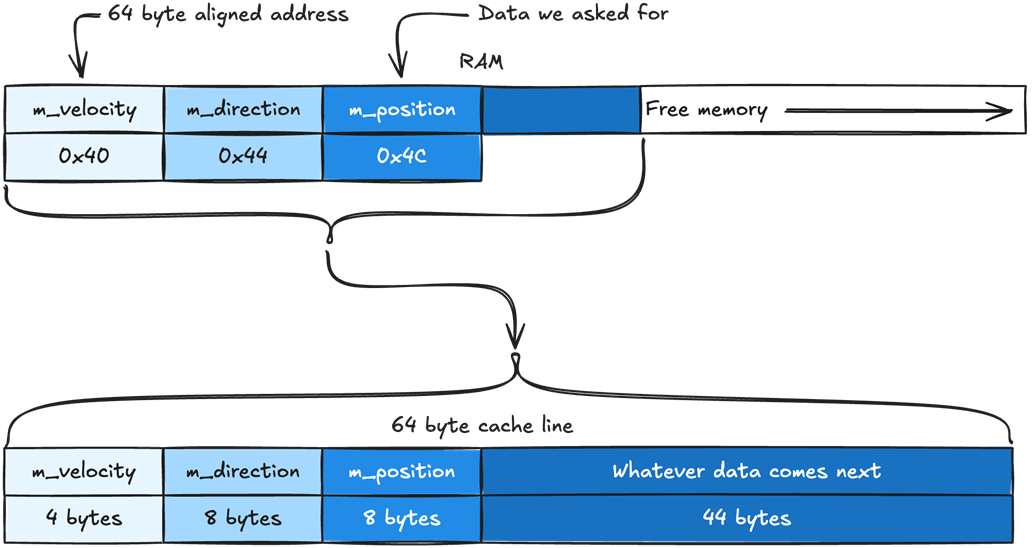

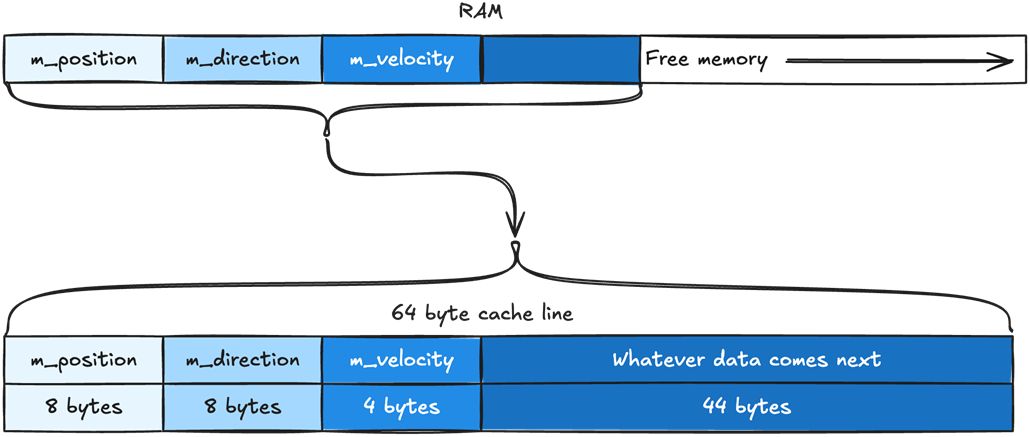

How the member variables of our Enemy object are placed in memory. The position data is placed first, then direction, then velocity. The same order they are defined in the Enemy class. They are packed together in memory without any space between them.

Our cache line will include m_position, m_direction, m_velocity, and whatever data comes right after them. Our cache line is 64 bytes. The variables m_position and m_direction are of type Vector2, which takes 8 bytes. The variable m_velocity is a float, which takes 4 bytes. That means we have 44 bytes leftover, which are automatically filled with whatever data comes after m_velocity.

When our CPU asks for m_position, the Memory Management Unit (MMU) will try to fill the cache line from the nearest address that is aligned with the size of our cache line. If our cache lines are 64-byte long, the cache line will be filled with data from the nearest 64-byte aligned address. In this case, m_position sits at 0x4C and the nearest 64-byte aligned address will be 0x40.

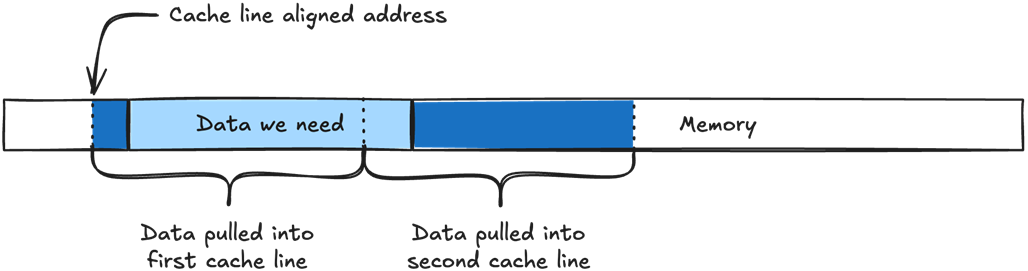

If the data we need does not align with the cache line size, it will need to be split into two cache lines instead of one.

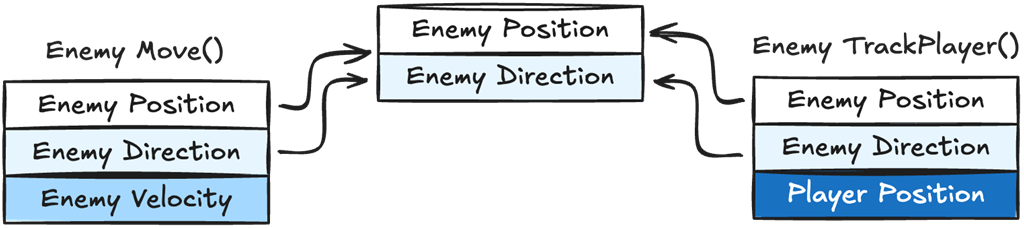

We can see both Move() and TrackPlayer() require the same variables, Enemy Position and Direction, but each one also needs different data as well, Enemy Velocity for Move() and Player Position for TrackPlayer(). When data is shared between different logic functions it makes it impossible to guarantee data locality for every logic function.

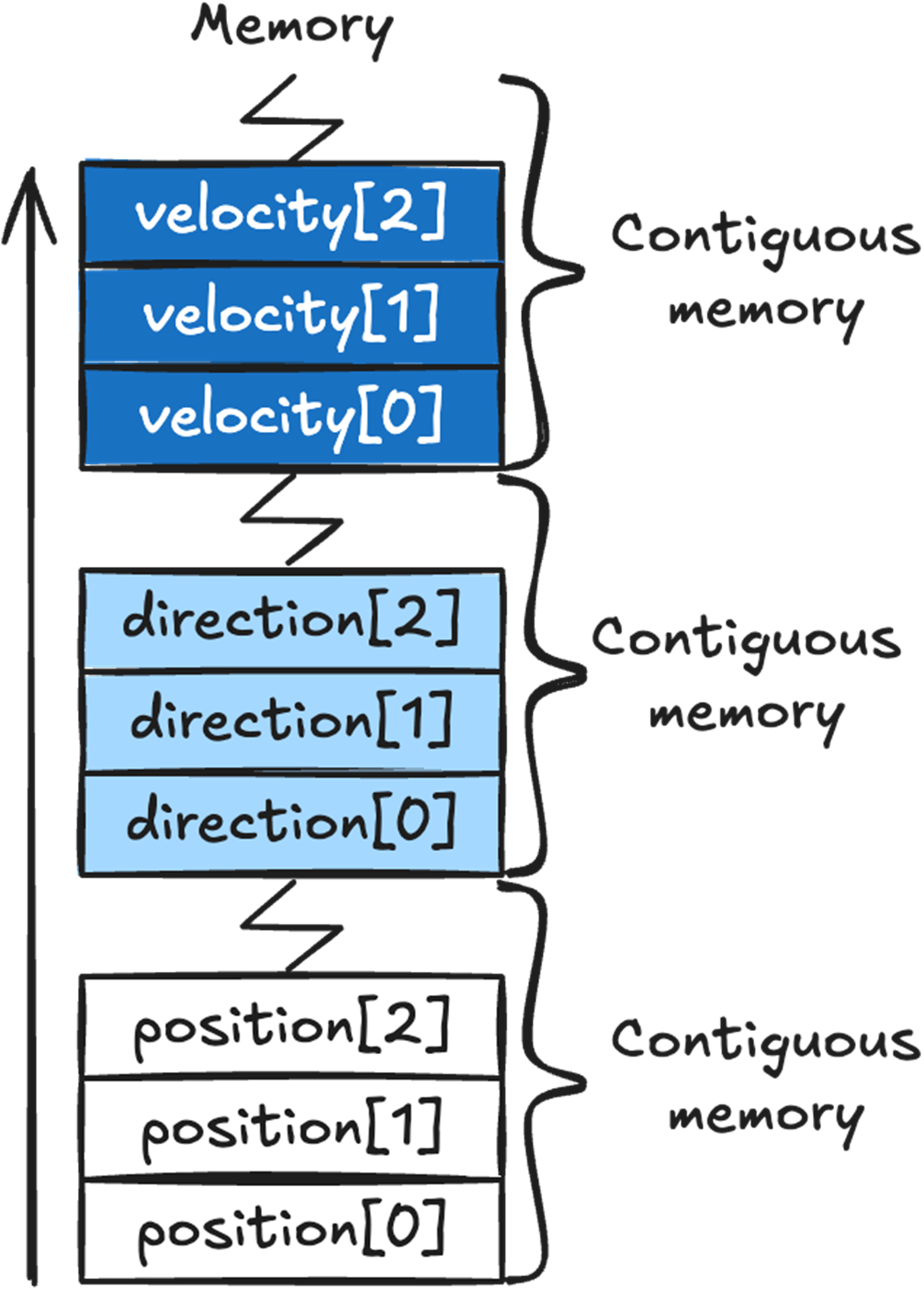

Arrays automatically place their data in contiguous memory. All the position array data will be in a single contiguous chunk of memory, as will direction and velocity’s data.

We can see how the position array sits in memory, and how the array elements 0 to 7 all fit in a single 64 byte cache line.

The two existing enemies in our game, the Angry Cactus, which is a static enemy, and the Zombie, which is a moving enemy.

Task to implement a new enemy, the Teleporting Robot.

Our game’s enemy inheritance tree, with EnemyTeleportOnHit inheriting from EnemyMove.

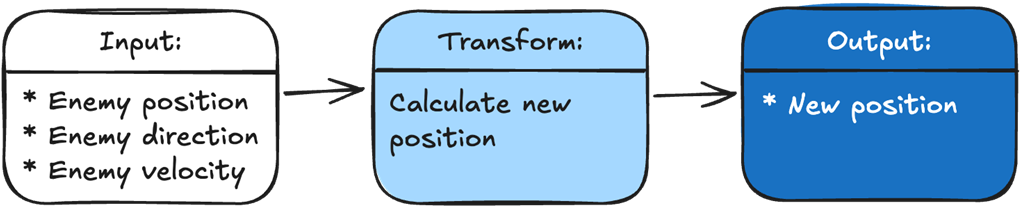

Every function in our game takes in some input data, then transforms it into output data.

The Move() function’s input is the enemy position, direction, and velocity. The transformation is our calculation of the new position. The output is the new position.

To make our enemy track the player, we just add a function that sets the enemy’s direction toward the player. Our input is the enemy position and the player position. The transformation is calculating a new direction for the enemy. The output is the new direction.

To add our new Robot Zombie, we just add a function that teleports the player to a new location if it is hit. Our input is the damage the enemy received, if any, and whether it should teleport if hit. The transformation is calculating a new position if the enemy is hit. The output is either the new position if hit, or the old position if the enemy is not hit.

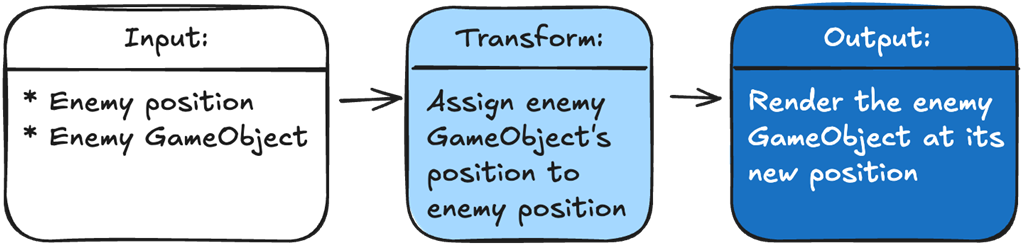

To show an enemy in the correct position, we pass in the enemy’s GameObject and its position. We transform our data by assigning the GameObject’s position to the enemy. The output is Unity rendering our GameObject in the correct position.

Task to implement a new enemy, the Zombie Duck.

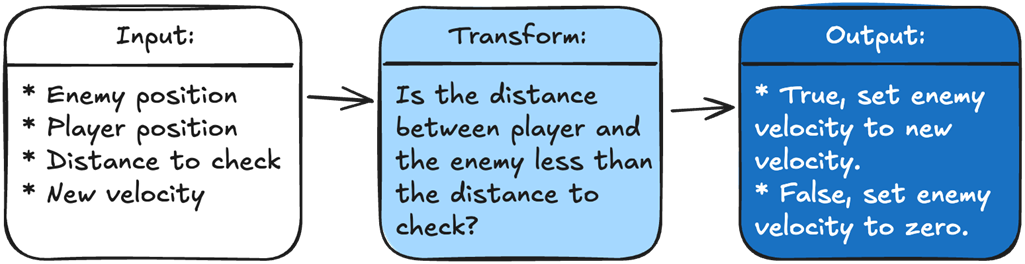

To determine what velocity we should set our enemy, we are going to take in four variables: the enemy position, the player position, the distance we need to check against, and the new enemy velocity. Our logic will calculate the distance between the player and the enemy and check it against the input distance. The output is the new velocity for the enemy based on the logic result.

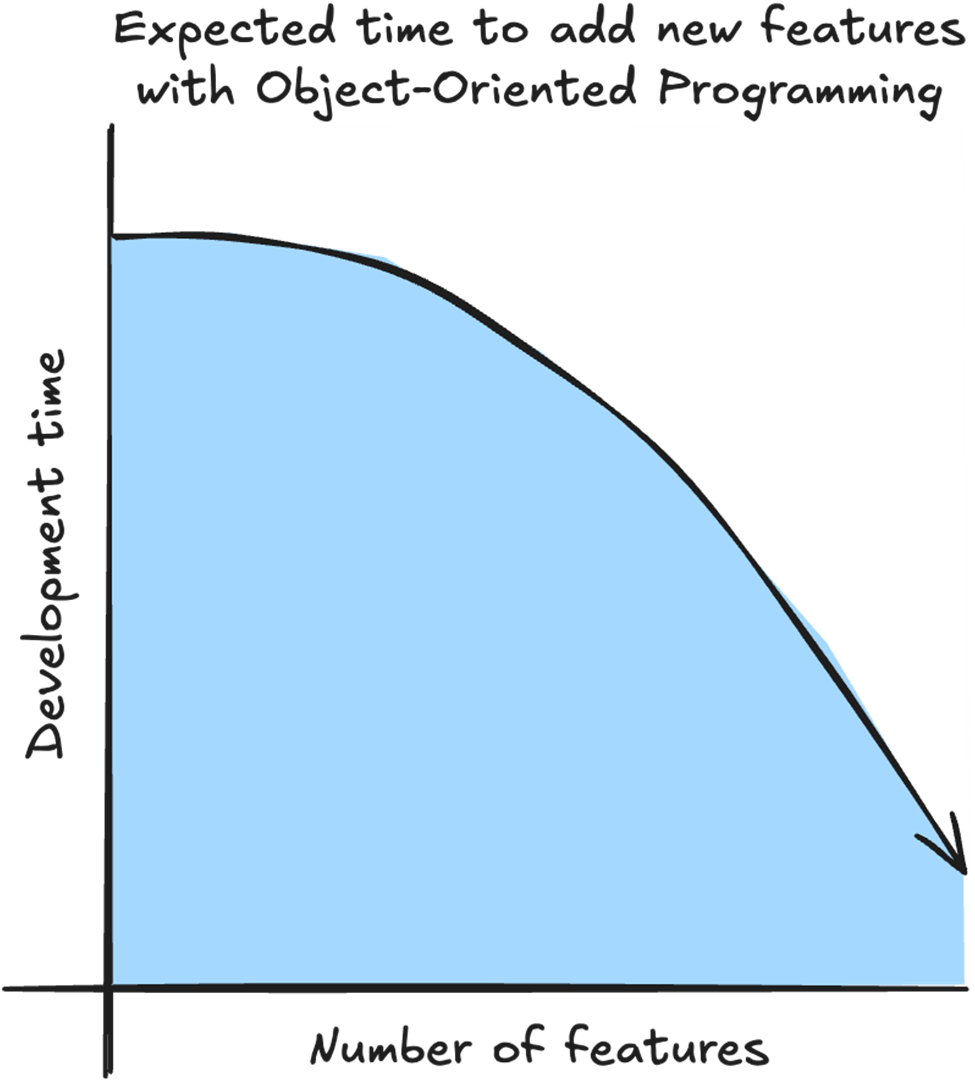

With OOP, in an ideal situation, we start the project by spending time setting up systems and inheritance hierarchies so future features will be quick and easy to implement.

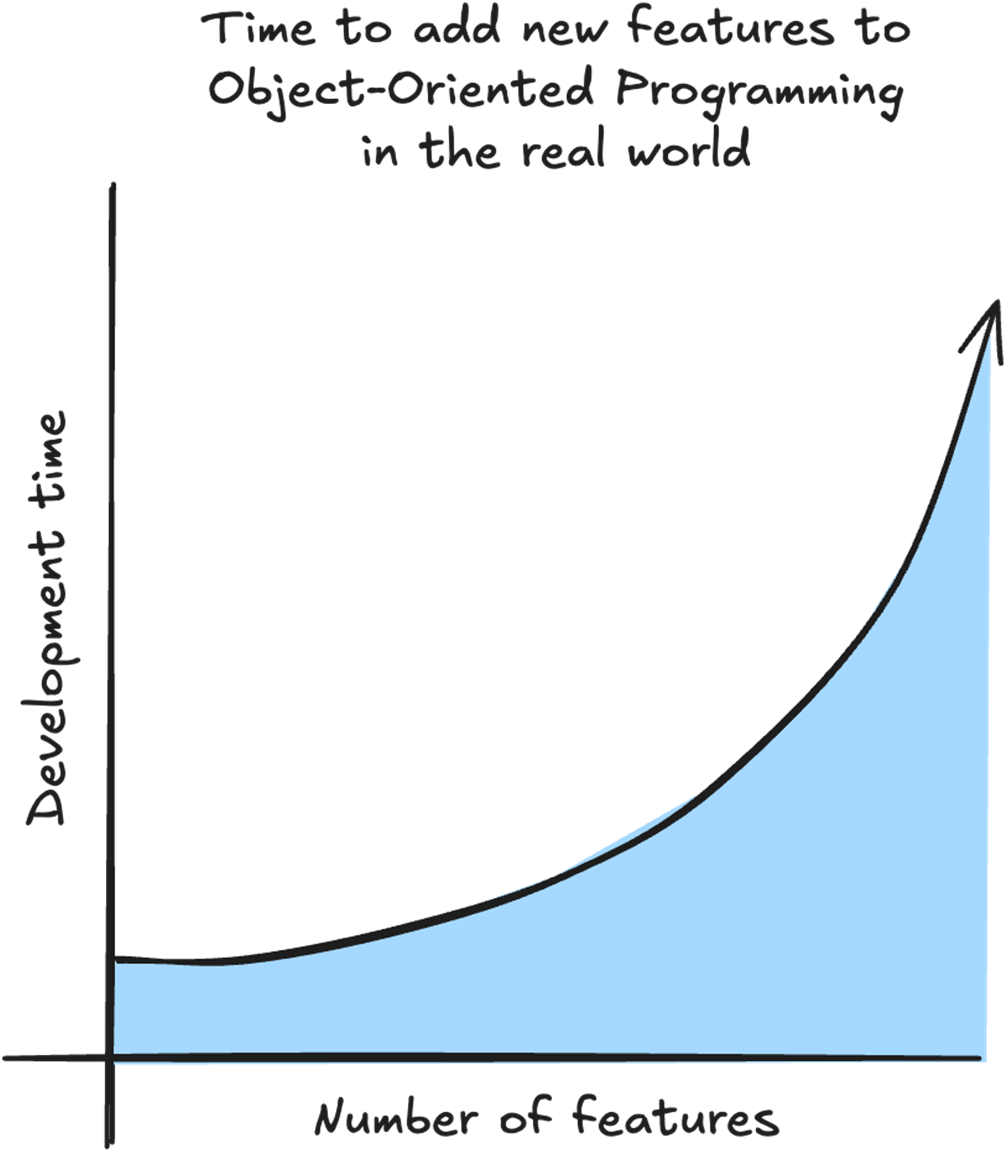

With OOP, what usually happens is that the more features we already have, the longer it takes to add a new feature. For every new feature, we need to take into account the complicated relationship between existing features.

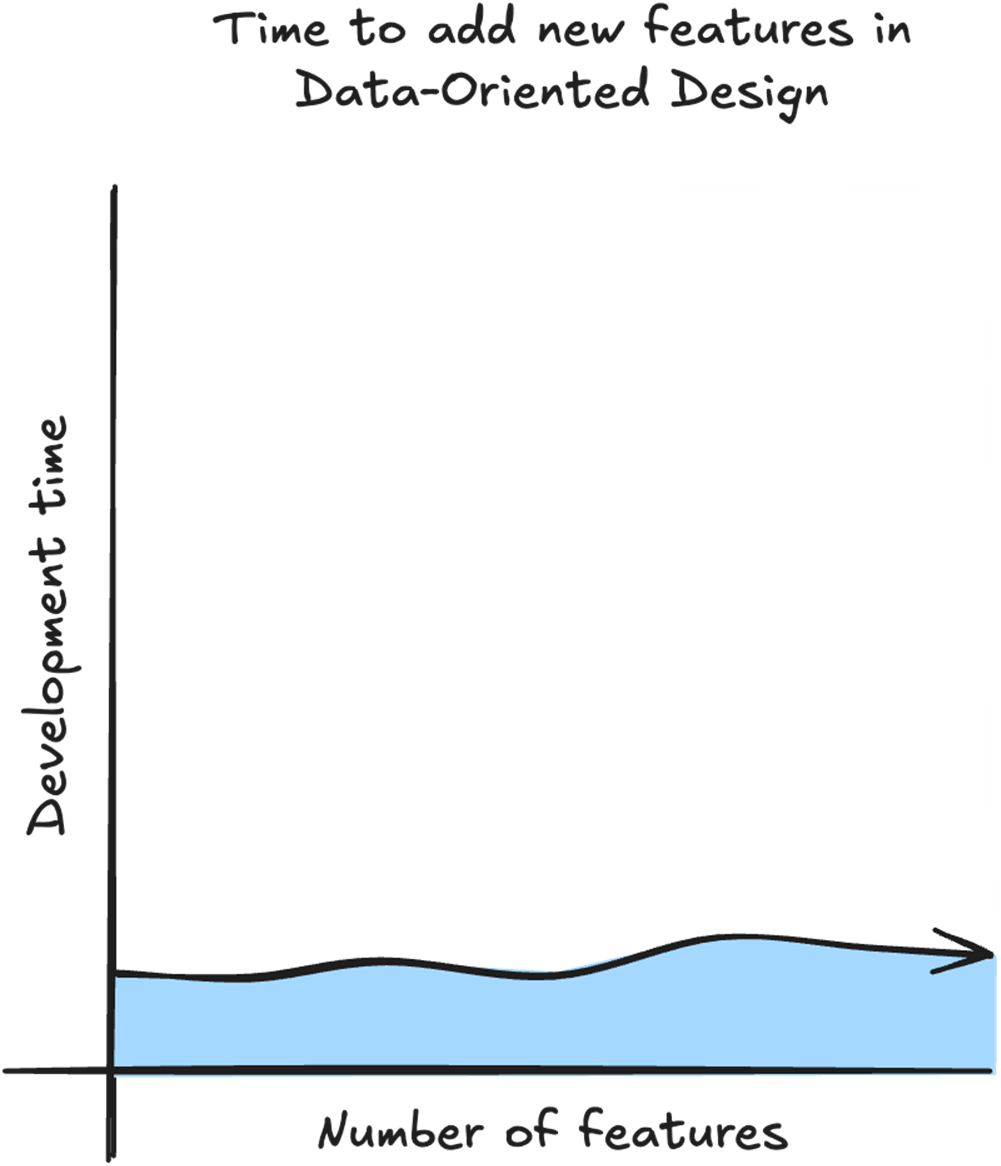

With DOD the time to add a new feature is linear because we don’t need to take into account the existing features. All we need is the data for the feature, and what logic we need to transform the data.

Summary

- With Data-Oriented Design we get a performance boost by structuring our data to take advantage of the CPU cache.

- Your target CPU may have multiple levels of cache, but the first level, called the L1 cache is the fastest.

- The L1 cache is the fastest because it is small and is placed directly on the CPU die.

- Retrieving data from L1 cache is up to 50 times faster than accessing main memory.

- To avoid having to retrieve data from main memory, our CPU uses cache prediction to guess which data we are going to need next and places it in the cache ahead of time.

- Data is pulled from memory into the cache in chunks called cache lines.

- Practicing data locality by keeping our data close together in memory helps the CPU cache prediction retrieve the data we’ll need in the future into the L1 cache.

- Placing our data in arrays makes it easy to practice data locality.

- With Data-Oriented Design we can reduce our code complexity by separating the data and the logic.

- Every function in our game takes input and transforms it into the output needed. The output can be anything from how many coins we have to showing enemies on the screen.

- Instead of thinking about objects and their relationships, we only think about what data our logic needs for input and what data our logic needs to output.

- With Data-Oriented Design, we can also improve our game's extensibility by always solving problems through data. This makes it easy to add new features and modify existing ones.

- Regardless of how complex our game has become, every new feature can be solved using data. This allows for near-constant development time regardless of how complex our game has become and makes it easy to add complicated new features.

- ECS is a design pattern sometimes used to implement DOD. Not all ECS implementations are DOD, and we don’t need ECS to implement DOD.

FAQ

What is Data-Oriented Design (DOD)?

DOD is a coding style that solves problems by focusing on data first: organize data by how it’s used, keep it contiguous in memory for cache efficiency, and write logic as functions that transform input data into output data, separate from the data itself.How is DOD different from Object-Oriented Programming (OOP)?

- OOP groups data and behavior into objects and models relationships (inheritance/trees).- DOD separates data from logic, groups data by usage, and favors contiguous layouts (like arrays) to maximize cache hits and performance.

- In games, where features change often, DOD avoids complex inheritance webs and keeps additions straightforward.

Why isn’t DOD “premature optimization”?

DOD is not a late-stage tweak; it’s a way of writing code that’s naturally performant from day one. In games, discovering performance issues late can force risky refactors or delays. With DOD, common hot paths are already cache-friendly, so you avoid many future optimization crises.How do CPU caches affect performance, and how does DOD leverage them?

The CPU retrieves data fastest from L1 cache (about 1–2 ns) and much slower from main memory (about 50–150 ns). DOD arranges data to increase cache hits—processing contiguous data in tight loops—so the CPU spends less time waiting on memory and more time executing logic.What is a cache line and why does it matter?

A cache line is a fixed-size chunk (often 64 bytes, CPU-dependent) that the CPU loads at once. If the data you’ll use next sits next to what you just loaded, it “comes along for free.” DOD aims to keep frequently co-used fields/elements in the same cache line to minimize cache misses.What is data locality, and how can I improve it in game code?

Data locality means placing data that’s used together close together in memory.- Prefer arrays of values you iterate over each frame (positions, directions, velocities).

- Process many items in batch functions (e.g., MoveAllEnemies).

- Keep frequently co-used data small and contiguous; split rarely used or unrelated data.

Why does DOD reduce code complexity?

By separating data and logic, you write small, purpose-driven functions that transform inputs to outputs without worrying about object hierarchies. You avoid inheritance trees and tangled relationships, making code easier to read, test, and reason about.How does DOD improve extensibility over long projects?

Adding a feature mainly means: identify the data it needs, add/extend the data containers (often arrays), and write a function that transforms inputs to outputs. The cost of adding the 100th feature is similar to the first because you don’t fight a growing inheritance tangle.What is ECS and how does it relate to DOD?

Entity Component System (ECS) is a design pattern that fits DOD well: Entities are IDs, Components are data, Systems are logic. ECS itself isn’t about caches, but it makes it easy to keep large data sets contiguous and process them in systems. You can use DOD with or without ECS.When should I prefer arrays (SoA) over objects (AoS), and how do I start applying DOD?

- Prefer arrays/SoA when you process many similar items every frame; this maximizes cache hits and enables tight loops and vectorization.- AoS can be fine for small, infrequently touched data.

- Getting started: identify hot loops, extract their input data into contiguous arrays, write batch functions that transform the arrays, measure cache misses/hits, and iterate.

Data-Oriented Design for Games ebook for free

Data-Oriented Design for Games ebook for free