1 Starting a fabulous adventure

This opening chapter sets the tone for a pragmatic, joyful tour of data structures and algorithms by asking what makes some of them feel “fabulous.” The author highlights qualities such as solving real problems beyond standard libraries, embracing counterintuitive ideas like immutability for undo/redo, spotting cross-domain patterns (e.g., backtracking powering tree search, map coloring, Sudoku, and pretty printing), writing code that expresses meaning rather than mechanisms, and delighting in designs that seem like “magic” at first glance. Along the way, the chapter celebrates leveraging language features to the fullest (with C# generics as a recurring star), reframing problems for dramatic gains (e.g., HashLife for cellular automata), connecting practice to theory, and keeping a sense of fun at the center of learning.

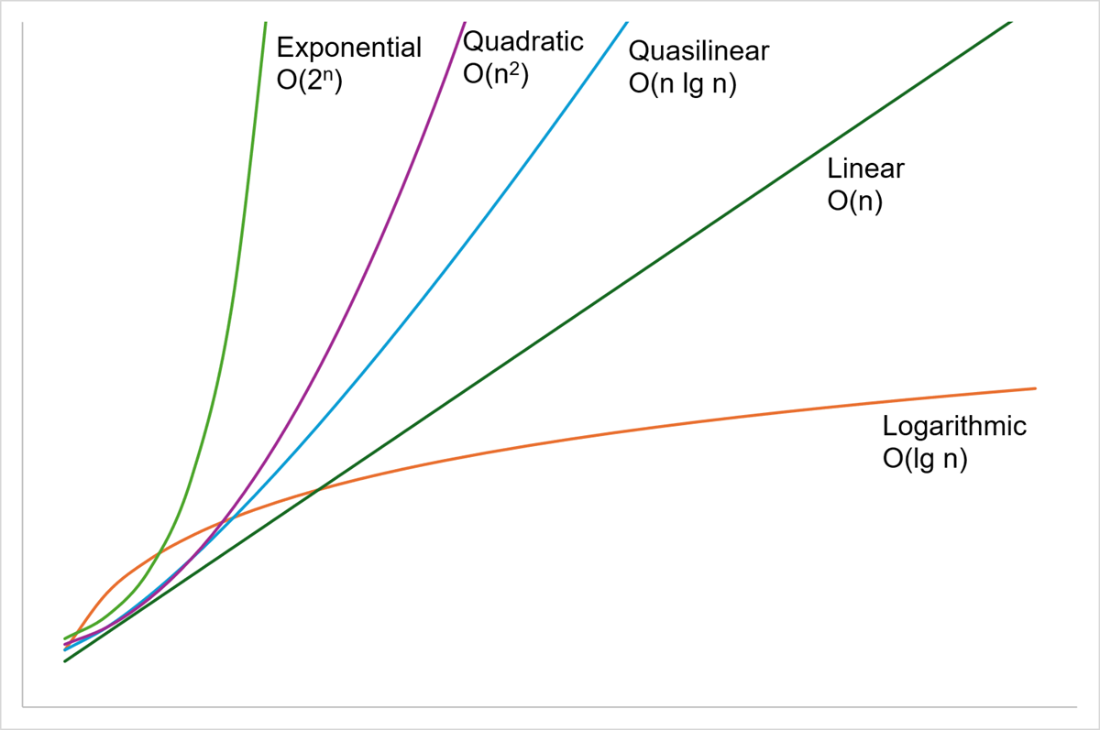

The chapter briefly defines core terms: a data structure organizes information; an algorithm is a finite process for solving a problem; and complexity relates problem size to cost in time, memory, or other resources. It reviews big-O notation with familiar tiers—constant, logarithmic, linear, quasilinear, quadratic, and intractable exponential/factorial—and stresses that costs can be context-dependent: best-, average-, and worst-case matter, as do non-time resources. Importantly, asymptotically superior algorithms aren’t always better for real workloads; simple “naïve” approaches can be fastest on typical, small inputs.

To ground these ideas, the chapter builds an immutable linked list in C#, then inspects its performance and design choices: representing an empty list as a valid object, pitfalls in automatically generated equality (including recursion risks), and the classic accidentally quadratic string concatenation in ToString. A straightforward Reverse method produces a new list in O(n) time and extra memory, illustrating how to reason about costs in immutable settings. The roadmap ahead promises twists on classic structures (stacks, queues, trees), techniques like persistence and memoization, elegant list reordering, a surprising near-constant-time reversal, backtracking for graph coloring and pretty printers, unification and anti-unification, and a practical toolkit for randomness, probability, and Bayesian inference—plus brief, accessible forays into theory—all written in C# but broadly applicable across languages.

A graph comparing the growth curves for logarithmic, linear, quasilinear, quadratic and exponential growth. Logarithmic is the shallowest curve, growing very slowly, and exponential is the fastest.

Summary

- There are lots of books about standard data structures such as lists, trees and hash tables, and the algorithms for sorting and searching them. And there are lots of implementations of them already in class libraries. In this book we’ll look at the less well-known, more off-the-beaten-path data structures and algorithms that I had to learn about during my career. I’ve chosen the topics I found the most fabulous: the ones that are counterintuitive, or seemingly magical, or that push boundaries of languages.

- I had to learn about almost all the topics in this book when I needed a new tool in my toolbox to solve a job-related problem. I hope this book saves you from having to read all the abstruse papers that I had to digest if you too have such a problem to solve.

- But more important to me is that all these fabulous adventures gave me a deeper appreciation for what computer programmers are capable of. They changed how I think about the craft of programming. And I had a lot of fun along the way! I hope you do too.

- Asymptotic complexity gives a measurement of how a solution scales to the size of the problem you’re throwing at it. We generally want algorithms to be better than quadratic if we want them to scale to large problems.

- Complexity analysis can be subtle. It’s important to remember that time is not the only resource users care about, and that they might also have opinions on whether avoiding a bad worst-case scenario is more or less important than achieving an excellent average performance.

- If problems are always small, then asymptotic complexity matters less.

- Reversing a linked list is straightforward if you have an immutable list! We’ll look at other kinds of immutable lists next.

FAQ

What does this chapter mean by “fabulous” algorithms and data structures?

They’re solutions that solve real problems off the beaten path, yield counterintuitive wins (like using immutability for undo/redo), transfer across domains, emphasize high-level meaning over low-level mechanisms, feel like “magic tricks,” exploit language features deeply, reframe problems for big gains, connect to theory, and keep programming fun.How does the chapter define a data structure and an algorithm?

A data structure is an organized way to store information. An algorithm is a finite sequence of steps that solves a problem; it can be nondeterministic, need not run on a computer, and can be conceptually simple even if it does lots of work.What is algorithmic complexity and why use Big-O notation?

Complexity relates problem size to resource cost (time, memory, etc.). Big-O describes how cost grows as input size grows, letting you compare scalability independent of hardware or constant factors.What common Big-O classes does the chapter highlight?

- O(1): constant work (e.g., read the first array element). - O(log n): grows slowly with size doubling (e.g., identifier length vs. count). - O(n): cost doubles with input doubling (e.g., summing n integers). - O(n log n): typical for good sorts; slightly more than linear. - O(n²): “accidentally quadratic” patterns like naive string concatenation; avoid at scale. - O(2ⁿ), O(n!): intractable beyond tiny inputs.Does the “best” asymptotic algorithm always win in practice?

No. For typical, small inputs a simpler algorithm with worse worst-case complexity can be faster. The chapter’s string-search anecdote shows that input characteristics and constants matter as much as big-O.How is problem size and cost chosen when analyzing complexity?

Pick a size metric that matches the algorithm (e.g., number of items; sometimes tree height, not node count). Consider the relevant costs: time, memory, and best/average/worst-case time, as appropriate.What immutable linked list representation does the chapter use, and what are its trade-offs?

It uses a record withValue and Tail, plus a singleton Empty instance where both are null. It’s concise but allows invalid states (a non-empty node with null tail) and relies on careful usage; a safer empty representation comes later.What performance pitfalls were found in the initial list implementation?

-IsEmpty was expensive due to record-generated value equality; prefer IsEmpty => Tail == null. - Records generate value equality that is O(k) in matching prefix length and recursive, risking stack overflow on long lists; provide an iterative custom equality if needed. - ToString did naive string concatenation, making it O(n²) in time and extra memory; use a StringBuilder for O(n). Fabulous Adventures in Data Structures and Algorithms ebook for free

Fabulous Adventures in Data Structures and Algorithms ebook for free