1 When a hello isn’t hello

JavaScript feels approachable because you can write a few lines and see them run immediately, yet the language and its runtimes hide deep complexity. This chapter introduces that hidden machinery and sets expectations for the rest of the book: you’ll learn how the language, the engine, and the host runtime each shape program behavior; how scheduling, the event loop, and multiple task queues interact; and why understanding these internals is essential for correctness and performance. The goal is to build intuition about what really happens when code executes so you can diagnose issues that aren’t obvious from surface-level knowledge.

A small “Hello” puzzle exposes the core theme: identical code can produce different outputs across environments because runtimes schedule asynchronous work differently. Node.js in CommonJS mode, Node.js as ECMAScript modules, Deno, and Bun each drain queues like nextTick, microtasks, timers, and immediates in their own orders, and even a file extension change can affect results. These variations aren’t mere curiosities; they arise from differing design goals and histories of each runtime. The lesson is to avoid depending on precise timing between queues and to recognize that many observable behaviors are host-defined rather than language-defined.

The chapter also clarifies roles: engines parse, compile, and execute code, while host runtimes embed engines, expose capabilities (timers, I/O, networking), and decide when JavaScript runs via an event loop. Although JavaScript executes one piece of code at a time, runtimes create the illusion of asynchrony by scheduling tasks across multiple queues, with microtasks governed by the language but drained at host-defined points. Alongside runtime nuances, the chapter previews language quirks (like floating-point and coercion oddities) and outlines the path ahead: starting from types and moving through promises, streams, cryptography, and module systems, using Node.js 24 as a baseline and contrasting other environments to explain why “hello” isn’t always “hello.”

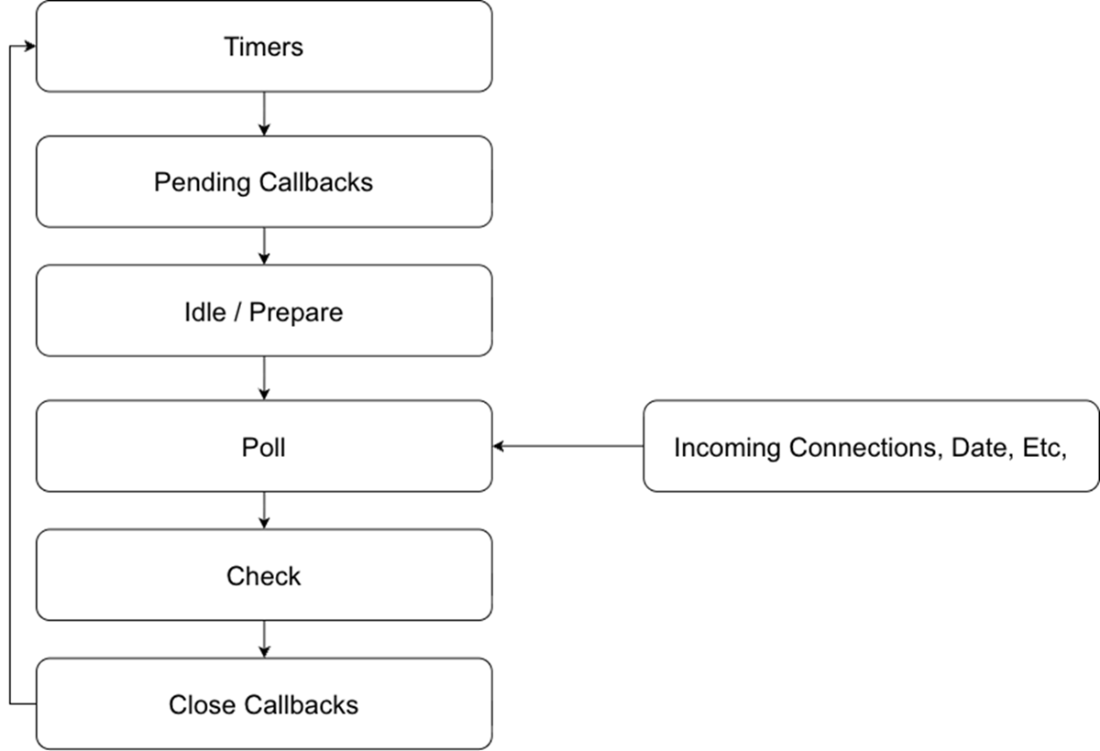

An illustration of the phases of the Node.js Event Loop from the project documentation (https://nodejs.org/en/learn/asynchronous-work/event-loop-timers-and-nexttick). At the start of each iteration Node.js will first execute timers, then move on to calling pending callbacks, preparing for I/O, polling the operating system for I/O, then performing various checks and cleanup operations before starting over again at the top with timers.

Summary

- Identical JavaScript code can yield different results in Node.js, Deno, and Bun due to differences in runtime implementation choices

- The event loop controls execution order, with each runtime implementing different scheduling priorities

- Language specifications define what must be consistent; implementations and hosts define what can vary

- Understanding the distinction between language, implementation, and host behaviors prevents unexpected bugs

FAQ

What is the core takeaway of “When a hello isn’t hello”?

The same JavaScript can produce different outputs across runtimes and even across module systems within the same runtime, because event loops, task queues, and startup rules are host-defined. The chapter’s goal is to build a deep understanding of those underlying mechanics so you can predict and control behavior, performance, and portability.Why does the “Hello” puzzle print different outputs in Node.js, Deno, and Bun (and between CommonJS and ESM)?

- Each runtime (and module system) schedules tasks differently: when to drain microtasks, how to prioritize process.nextTick, when setImmediate runs, and how startup/teardown works.- Node.js CommonJS drains nextTick then microtasks before the event loop starts, yielding “Hello”.

- Node.js ESM initializes differently and drains queues in another order, yielding “elHo” then a final “l” on the next turn.

- Deno defaults to web-style semantics and doesn’t expose setImmediate globally, changing both availability and timing (after importing setImmediate, the order still differs).

- Bun uses JavaScriptCore and its own scheduling choices, so the printed order differs yet again.

What are microtasks, nextTicks, and immediates, and how does Node.js handle them?

- Microtasks: Language-defined queue used by promises and queueMicrotask. Runtimes choose when to drain it, often many times per loop turn.- process.nextTick: Node-specific queue that runs before other microtasks at well-defined points in Node’s lifecycle.

- setImmediate: Node-specific callback queue processed in the “check” phase (after timers/poll).

- Ordering is host-defined: Node typically drains nextTick first, then microtasks, then proceeds through event loop phases.

What is the event loop and why does it differ across runtimes?

The event loop is the scheduler that runs JavaScript in response to events. Browsers tune it for UI responsiveness (animation frames, user input), while Node.js tunes it for system I/O (timers, network, filesystem) and divides work into phases (timers, pending callbacks, poll, check, close). Those priorities and checkpoints lead to observable differences in when callbacks run.What’s the difference between a JavaScript engine and a host runtime?

- Engine: Parses, compiles, and executes ECMAScript (e.g., V8 by Google, SpiderMonkey by Mozilla, JavaScriptCore by Apple). Engines aim for spec-consistent observable behavior.- Host runtime: Embeds an engine and provides environment features (event loop, timers, I/O, globals). Examples: Node.js and Deno (V8), browsers like Chrome (V8), Firefox (SpiderMonkey), Safari/Bun (JavaScriptCore). The host decides scheduling and available APIs.

What do language-defined, implementation-defined, and host-defined mean?

- Language-defined: Specified by ECMAScript; behavior must be consistent across environments (e.g., promises’ observable behavior, microtask semantics).- Implementation-defined: Details may vary across engines but are consistent within one engine family (e.g., some optimization strategies).

- Host-defined: Determined by the runtime embedding the engine (e.g., process.nextTick, setImmediate, event loop phases and timing).

How can the Node.js module system (CommonJS vs ESM) change the output order?

Node bootstraps CommonJS and ESM differently. That changes when it drains nextTick and microtasks relative to starting the event loop and module initialization work. The altered startup sequence leads to different observable scheduling, so identical code can produce different orders purely by switching file extension (.js vs .mjs).If JavaScript is single-threaded, how does it do “asynchronous” work?

The host runtime schedules work via queues. External events (timers, I/O, UI) enqueue tasks; the event loop picks them up one at a time. Microtasks (e.g., promise continuations) are drained at specific checkpoints between tasks. This sequencing creates the illusion of concurrency while keeping execution single-threaded per event loop thread.Why is relying on exact callback ordering risky?

Because ordering between queues (nextTick, microtasks, timers, immediates) is host-defined and can change across runtimes, versions, and even module systems. Code that depends on a specific inter-queue ordering may break or slow down when ported or upgraded.How can I write more portable and predictable async code?

- Prefer language-defined constructs (promises, queueMicrotask) over host-only APIs when portability matters.- Avoid depending on ordering between different queues; treat cross-queue timing as unspecified.

- Keep callbacks small and non-blocking; don’t starve the loop.

- Test across target runtimes and versions; document assumptions (e.g., Node 24+, ESM vs CJS).

- For Node-specific behavior you rely on, isolate it and guard with feature checks.

JavaScript in Depth ebook for free

JavaScript in Depth ebook for free