1 Making programs safer

Software is inherently risky because even small defects can cause huge losses, and traditional, stateful, effectful styles make programs unpredictable. This chapter argues for humility about our limits as developers and for adopting practices that shrink the bug surface: avoid mutable state and ad‑hoc control flow, eradicate nulls, confine interactions with the outside world, and minimize complexity through deliberate simplicity. The overarching goal is to make programs deterministic, easier to reason about, and safer in production by isolating the few unavoidable unsafe parts from the many safe ones.

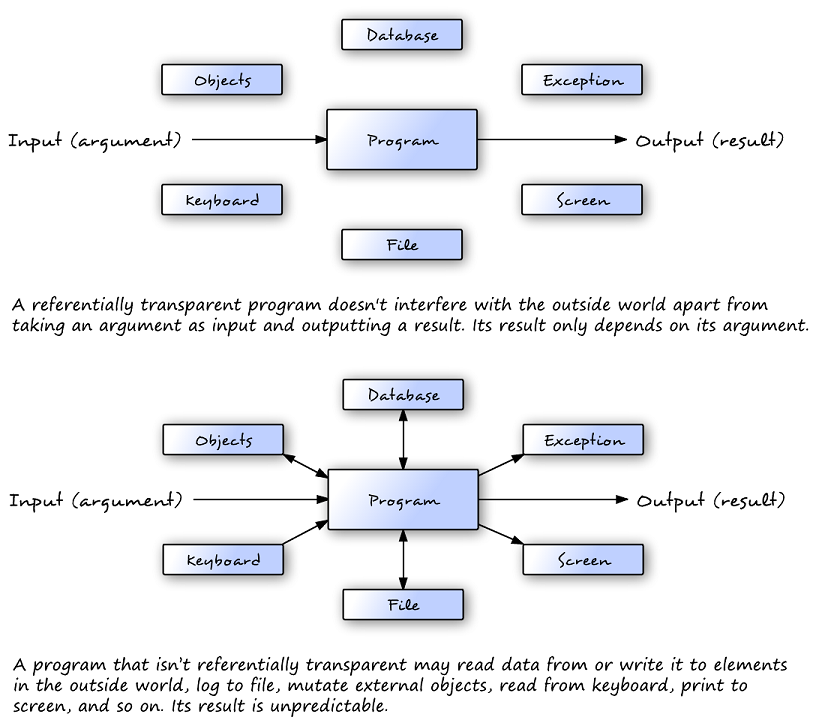

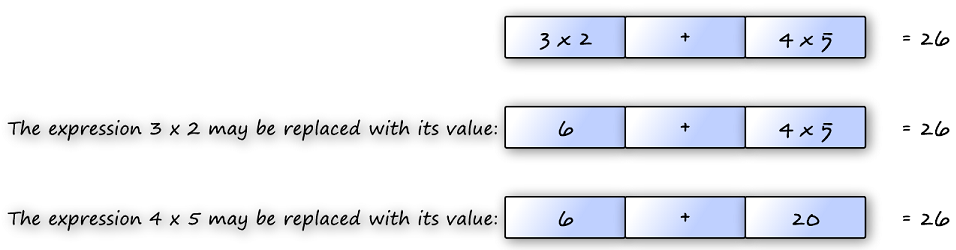

A key theme is controlling effects. Effects include any interaction beyond a function’s scope—printing, file or network I/O, database calls, or mutating shared state. The chapter promotes composing small, pure functions that take inputs and return values, separating effect evaluation from core logic. Referential transparency—code that neither depends on nor mutates external state—yields determinism, reusability, and freedom from hidden failure modes (like unavailable devices or stale shared data). With purity, developers gain powerful reasoning tools such as the substitution model, and reap practical benefits: simpler testing without mocks, stronger modularity, safer concurrency through immutability, and easier composition of programs from reusable parts.

These ideas are made concrete by refactoring an example purchase flow. Instead of charging a credit card inside the function (a side effect), the function returns both the domain result and a Payment description, allowing the system to test logic without external calls and to flexibly batch or defer charges. The chapter then shows how standard collection operations (grouping, mapping, reducing) enable concise, testable composition without loops or shared mutation, and how pushing abstraction—generalizing patterns like reduce to fold and reusing library operations—removes repetition and prevents entire classes of bugs. In short, by privileging purity, referential transparency, and abstraction, Kotlin programs become safer, more predictable, and easier to evolve.

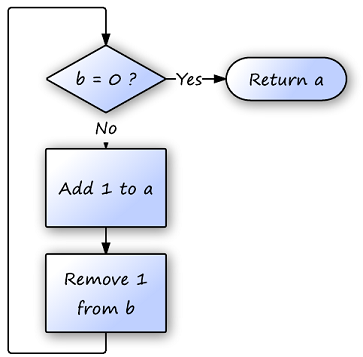

Figure 1.1. A flow chart representing a program as a process that occurs in time. Various things are transformed and states are mutated until the result is obtained.

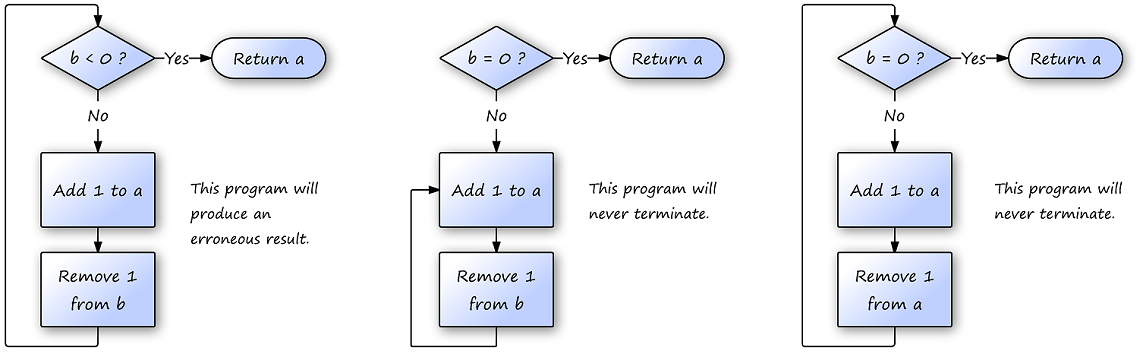

Figure 1.2. Three buggy versions of the same program

Figure 1.3. Comparing a program that’s referentially transparent to one that’s not

Figure 1.4. Replacing referentially transparent expressions with their values doesn’t change the overall meaning.

Summary

- You can make programs safer by clearly separating functions, which return values, from effects, which interact with the outside world.

- Functions are easier to reason about and easier to test because their outcome is deterministic and doesn’t depend on an external state.

- Pushing abstraction to a higher level improves safety, maintainability, testability, and reusability.

- Applying safe principles like immutability and referential transparency protects programs against accidental sharing of a mutable state, which is a huge source of bugs in multithreaded environments.

FAQ

Why does the chapter claim programming is “dangerous”?

Because small defects can trigger very large failures and costs. Historical incidents (for example, date handling and arithmetic overflows) illustrate how a single bug can crash systems or waste billions. The chapter argues for techniques that reduce entire classes of defects and confine the rest to well-defined areas.What are “effects” and how do they differ from “side effects”?

Effects are any interactions with the outside world or outer scope (I/O, database writes, mutating shared state, etc.). A side effect is an observable effect that happens in addition to returning a value. Pure functions avoid both: they only compute and return results without altering or depending on external state.What is referential transparency?

Code is referentially transparent when its output depends only on its inputs and it neither relies on nor mutates external state. Such code is self-contained, deterministic, doesn’t throw recoverable exceptions, and doesn’t depend on external devices, making it predictable and reusable.How does referential transparency make programs safer and easier to test?

Deterministic functions are easier to reason about and can sometimes be proven correct. Tests need no mocks to isolate external systems because there are no effects to isolate—inputs and outputs suffice. This leads to simpler, faster, and more reliable tests.What is the substitution model, and why does it matter?

If an expression is referentially transparent, you can replace it with its value without changing program meaning. This enables equational reasoning: you can simplify and analyze programs by substituting calls with results. If a function performs effects (like logging), substitution changes behavior, revealing why effects hinder reasoning.Which practices does the chapter recommend to avoid common programming traps?

- Avoid mutable references; if mutation is unavoidable, abstract it once. - Prefer higher-level operations over explicit control structures (branching/looping). - Restrict effects to small, well-defined areas. - Don’t throw exceptions for control flow; use safer alternatives (covered later). - Eliminate nulls or confine them to clearly marked code paths.How should unavoidable effects be handled safely?

Separate effect description from effect execution. Return a representation of the effect (for example, a Payment object) alongside computed results, then evaluate effects at the boundary of the system. This keeps core logic pure and testable.What does the donut example demonstrate?

RefactoringbuyDonut to return a Purchase(donut, payment) removes the immediate credit-card charge side effect. You can test the logic without contacting a bank, batch or combine payments later, and choose when and how to execute effects at the edges of the system. The Joy of Kotlin ebook for free

The Joy of Kotlin ebook for free