1 Introduction to voice first

Voice-first computing moved from a long-held dream to a daily reality with devices like the Amazon Echo, shifting speech from niche, rigid phone trees to open, extensible platforms. This chapter defines voice first as systems primarily operated by voice and opened to third‑party development, bringing the breadth of the web to spoken interactions through skills and actions. It contrasts constrained IVR menus with flexible conversational experiences, highlights the rapid growth of Amazon, Google, and Microsoft ecosystems, and notes the emerging multimodal landscape where screens complement speech while keeping voice at the core.

Designing effective voice user interfaces means applying the principles of good conversation: provide just enough information, ask clarifying follow‑ups, respect context, and maintain an appropriate personality. Because audio can’t show long menus or lists, the burden shifts from users to designers and developers to anticipate needs, make options discoverable, and reduce cognitive load with concise prompts and confirmations. The aim is to help people achieve goals efficiently, handle unexpected inputs gracefully, and create dialogs that feel natural rather than mechanical or rigid.

Under the hood, a voice exchange unfolds in stages: a locally detected wake word begins streaming audio; speech is converted to text; natural language understanding maps utterances to developer‑defined intents and extracts variable details via slots; fulfillment code—often running on serverless platforms like AWS Lambda or Google Cloud Functions—executes logic and returns a response; and text‑to‑speech delivers it, optionally shaped with SSML for pacing, emphasis, and tone. The chapter explains why speech recognition is challenging, how sample utterances train the NLU, and why intents and slots resemble functions and arguments. With these building blocks and JavaScript/Node.js, developers can craft Alexa skills and Google Assistant actions that are powerful, natural, and enjoyable to use.

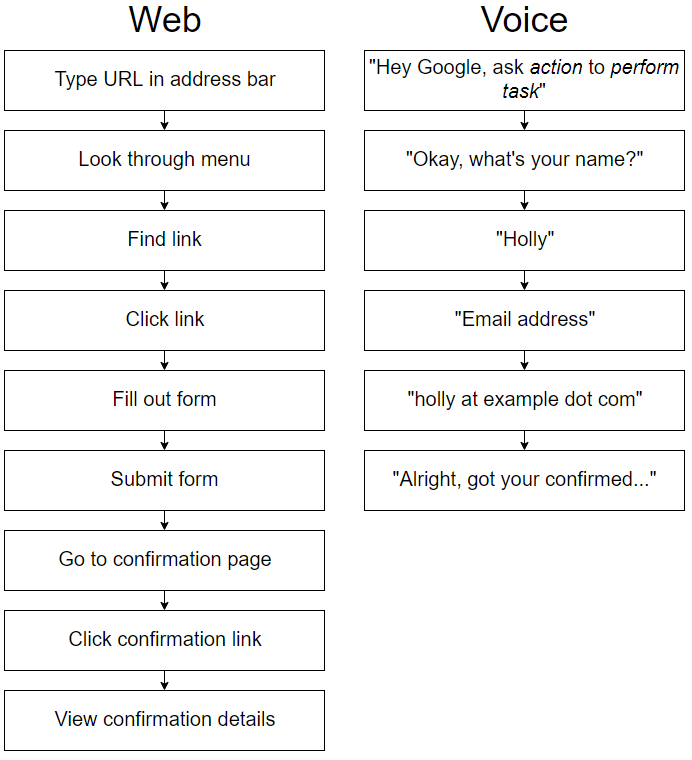

Figure 1.1. Web flow compared to voice flow

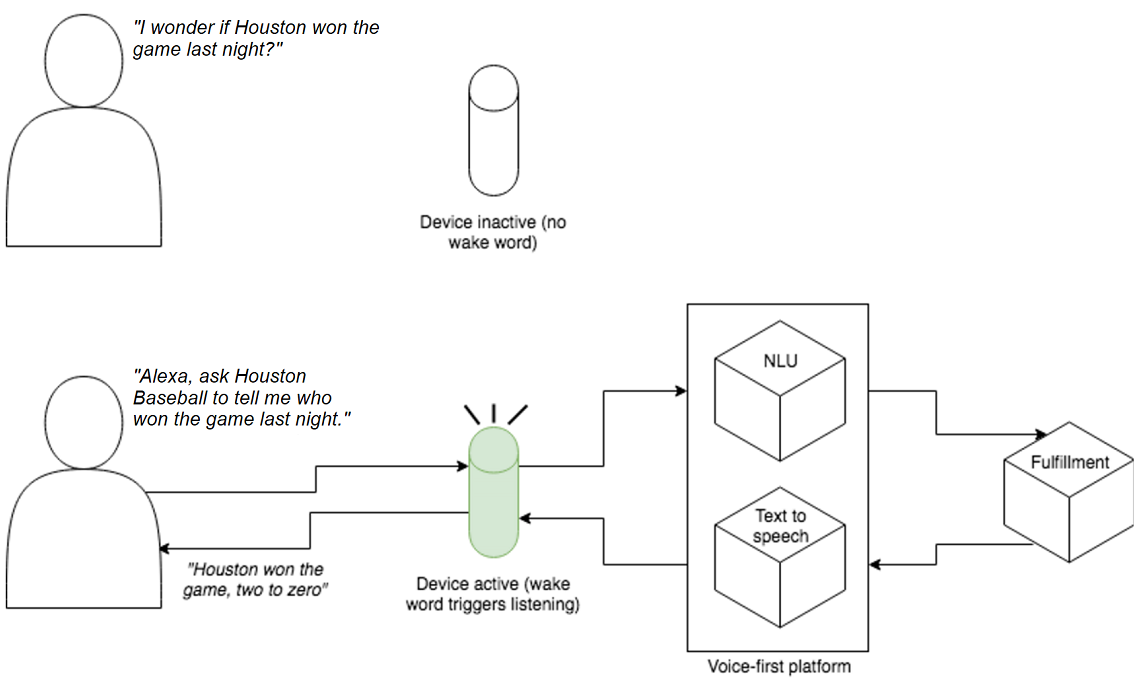

Figure 1.2. Alexa relies on natural language understanding to answer the user’s question.

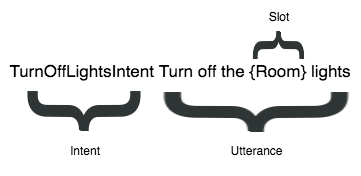

Figure 1.3. The overall user goal (the intent), the intent-specific variable information (the slot), and how it’s invoked (the utterance)

Summary

- Focus on taking the burden of completing an action from the user in voice-first applications.

- Data in a conversation flows back and forth between partners to complete an action.

- Building a voice application involves reliably directing this data between systems.

- Begin to think of requests in terms of intents, slots, and utterances.

FAQ

What does “voice-first” mean?

Voice-first platforms are designed to be used primarily through voice and are open to third‑party extensions built by developers. They emphasize natural, conversational interactions and allow developers to add new capabilities that feel like apps for voice.How are voice-first platforms different from legacy IVR phone trees?

- IVR systems guide callers down rigid decision trees with a small set of predefined choices.- Voice-first platforms support open-ended, natural conversation and can be extended with third‑party “skills” or “actions.”

- Rather than forcing users to navigate menus, voice-first systems infer intent and return concise, relevant results—often just one.

Who are the main voice-first platforms, and why isn’t Apple included?

Amazon (Alexa), Google (Assistant), and Microsoft (Cortana) are highlighted because they opened their platforms to third‑party developers. Although Siri and HomePod are popular, Apple did not (in the context of this chapter) open them broadly to third‑party voice app development.Is voice-first the same as voice-only?

No. Voice-first means voice is the primary interaction, not the only one. Devices like Echo Show or Google Assistant on screens (via Chromecast, smart displays, TVs) enable multimodal experiences that combine voice with visuals, while keeping voice at the center.What are intents, sample utterances, and slots?

- Intents: The actions a skill can perform (similar to functions in code).- Sample utterances: Example phrases that teach the NLU how users might express each intent.

- Slots: Variable pieces of information within an intent (like function arguments), often tied to a type (for example, a “Room” slot with values such as kitchen or living room).

How does a spoken request become a response?

- Wake word/phrase is detected locally (for speed and privacy).- Audio streams to the platform for speech-to-text (ASR).

- Natural language understanding (NLU) identifies the intent and extracts slot values.

- The request is sent to fulfillment (your code) to perform logic and gather data.

- The platform converts the response text (optionally with SSML) back to speech and plays it to the user.

What is fulfillment, and where does it run?

Fulfillment is the backend code that handles a user’s intent, runs business logic, calls APIs, and assembles the response. It commonly runs on serverless platforms like AWS Lambda (for Alexa) or Google Cloud Functions (for Google Assistant), returning a structured response the platform turns into speech.How do wake words work, and what about privacy?

Devices keep a short rolling audio buffer and locally detect wake words (e.g., “Alexa,” “Hey Google”). Only after the wake word is recognized do they begin streaming audio for processing. Local wake-word detection reduces latency and helps mitigate privacy concerns by limiting what’s sent to the cloud before activation.What principles make for good VUI (voice user interface) design?

- Be a helpful conversation partner: give just enough information, ask follow‑ups when needed, and handle misunderstandings gracefully.- Match tone and personality to the context (banking vs. entertainment).

- Use context to reduce unnecessary questions.

- Anticipate user needs and make options discoverable without overwhelming them.

Voice Applications for Alexa and Google Assistant ebook for free

Voice Applications for Alexa and Google Assistant ebook for free